Strategic Situation

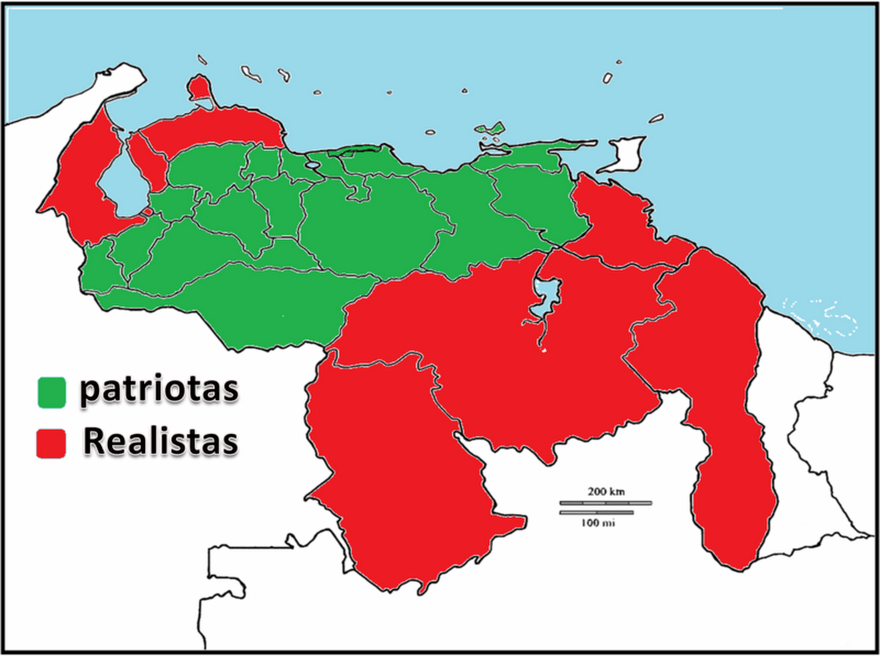

Activities in the year 1814 began in the provinces of

Mérida, Trujillo, Caracas, Cumaná, Barcelona and Margarita, under Republican

control, although a number of guerrilla groups that sided with the Monarchy

were also quite active with backing provided by Brigadier Ceballos from Coro

and by Brigadier Juan Manuel Cajigal, who arrived from Puerto Rico towards the

end of 1813, as well as other forces active in the eastern and central plains,

with support received from Guayana.

Domingo de Monteverde, having suffered serious injuries in

the fighting at Las Trincheras remained under siege at the fortress in Puerto

Cabello after, in command of the Granada Regiment and other troops.

A man whose name would later fill Republican hearts with

fear was already being mentioned on the plains of Guárico. He was General

Commander of the Calabozo Cavalry (appointed by Monteverde in January 1813),

and later head of the Royal Army of Barlovento, José Tomás Boves, who

controlled the area around San Juan de los Morros at the head of an army of

some 3,400 men, mostly on horseback. This army, made up mainly of plainsmen, or

llaneros, and slaves who were promised their freedom provided they rose up in

arms against their former masters and in exchange for a share of the booty, was

neither American nor Spanish, royalist or republican, but remained on the

sidelines of the clearly differentiated forces envisaged by Bolívar when he

issued his Decree of War to the Death (Trujillo, 15 June 1813), and would soon

spread terror throughout the territory held by the Republicans, with anarchy as

its banner and “Death to Whites” as its battle cry.

The first battle of La Puerta was fought on 3 February 1814.

It was fought in a pass in the mountains that stand between the plains and the

northern territory, a crossroads for routes joining north and south and leading

to the valleys of Aragua and the roads to Valencia and Caracas, a site of

strategic importance.

The forces sent by Bolívar to fend off the threat of Boves

totaled some 1,800 men, mainly infantry, under the orders of Vicente Campo

Elías who had defeated Boves a few months earlier in the fighting at

Mosquiteros, in Guárico (14 October 1813).

This time luck was not on Campo Elías’s side. The Republican

troops were trounced. The combination of cavalry and numerical superiority of

Boves’s forces was decisive for this victory, which would not be the last the

enemies of the Republic would be able to boast of on this battlefield.

Campo Elías and his surviving troops retreated northward to

the town of El Consejo and then, under orders from Bolívar, to La Cabrera,

where he joined forces with the men led by Lieutenant Colonel Manuel Aldao, who

had been ordered to defend the strategic mountain pass.

Boves, who had been seriously wounded at the Battle of La Puerta,

was forced to head back to the plains to recover from his wounds and raise more

troops. Before pulling back, he split his forces. One column led by Francisco Tomás Morales,

with 2,500 men (app. 1,800/cavalry + 900/infantry) who were supposed to move

north, take the town of Villa de Cura and continue on towards La Victoria in

order to cut off communications between Caracas and Valencia; and another under

the command of Francisco Rosete (app. 2,000 men, mostly cavalry), who were to

march to Caracas via the Tuy Valleys.

When Bolívar received the news of Campo Elías’s defeat at La

Puerta, he set off for Valencia with part of the forces that were laying siege

to Puerto Cabello, a strategic move that placed him at the “center” of the

field of operations, where he would be able to head over to Barquisimeto to

help Rafael Urdaneta or move to Caracas if necessary.

At the same time, Major General José Félix Ribas, as

Commander and Governor of the Province of Caracas, moved the troops under his

command, intending to reach the town of La Victoria so as to ensure that

communications between Caracas and Valencia were not disrupted.

The troops under Ribas consisted of:

1) The La

Guaira Infantry Battalion, under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Ramón Ayala

Soriano, consisting of close to 350 men.

2) The Superb

Dragoons of Caracas, led by Colonel Luis María Rivas Dávila, with close to 200

men.

3) An artillery

battery made up of five (5) pieces of artillery and approximately 150 men.

4) Eight

hundred (800) students from the university and seminary in Caracas.

5) 200

unattached men and recruits.

By the time they reached La Victoria on February 10, 1814,

they totaled some 1,500 men. (For information on the number of men, we

recommend the book El General en Jefe José Félix Ribas, pp. 120 and 121, by

General Héctor Bencomo Barrios).

The Battlefield

La Victoria is a town that runs from east to west, about

midway on the main road joining Caracas and Valencia, some 80 Km. from each

city. To the west of the city lies a natural boundary, the Aragua River that

crosses the road about one (1) kilometer from the town’s main square. To the

north, it borders on the hills known as El Calvario that stand between the town

and the Caribbean Sea. Other hills,

called the Pantanero Hills, lie to the south, separating the town from the

central plains, and to the west lays the road leading to the Caracas Valley.

Tactical Situation

Upon arriving at La Victoria, General Ribas began to prepare

his defense strategy, aware as he was that his inexperienced infantrymen would

be unable to stand up to the cavalry on open ground and could suffer the same

fate as Campo Elías at La Puerta. He positioned his advance troops close to the

river’s edge on the main road, and on the higher land at El Pantanero and El

Calvario, setting up a fortified perimeter around the main plaza and the church

in town. He set up the artillery pieces, dug trenches and built breastworks to

protect the Fusiliers and the Dragoons. This was how things stood when General

Ribas addressed his troops, with the rousing words quoted by Eduardo Blanco in

his book Venezuela Heroica:

Soldiers: The long awaited moment is here today: there is

Boves. The army he brings to do battle against us is five times larger; yet it

still seems too small to wrest victory from our hands. Defend the lives of your

children, the honor of your wives, the soil of the motherland from the fury of

tyrants; prove to them that we are all powerful. On this memorable day, we

cannot choose between death and victory: victory must be ours! Long live the

Republic!

In the other camp, Colonel Morales, who would rise to the

rank of field marshal and who had abandoned the positions he held in La

Victoria before the arrival of the Republican troops, preferred to attack

rather than be attacked given that most of his troops were cavalrymen. He

therefore split his forces into two (2) columns. The first, marching in from the

southwest along the El Pantanero road, consisted of seven hundred (700)

infantrymen, two thousand (2,000) men on horseback, and four (4) pieces of

light artillery. The other, consisting of two hundred (200) infantrymen and

five (500) hundred men on horseback, moved in along the main road. Boves was in

Villa de Cura, recovering from his wounds, with a reserve force.

This was the setting of a battle that could decisive for the

future of the Republic. A Republican defeat at La Victoria would open up the road

to Caracas through the Valleys of Aragua, leaving the city surrounded and at

the mercy of Boves’s troops; this city also faced a threat from the south,

where Rosete was marching towards Caracas at the head of a column of 2,000 men,

leaving terror in his wake as part of the War to the Death.

Written by

Carlos A. Godoy L.

In commemoration of the 200th anniversary of

The Battle of La Victoria.

Caracas, Venezuela. January 2014.