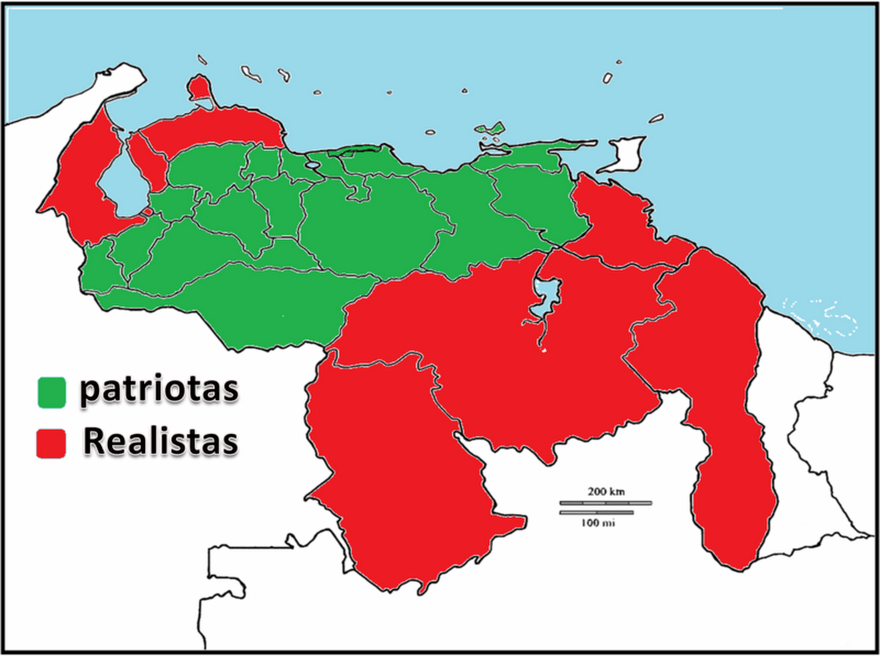

So with the kind help of Richard Clarke of Too Fat Lardies fame, we've managed to put together army lists for the South American Wars of Liberation to go with the realease of the wonderful new set of rules "Sharp Practice 2." The list give you many variations for both Patriot and Royalist forces fighting in the Northern Campaigns of Simon Bolivar in Colombia and Venezuela (1817 - 1824).

You can find them here:

http://toofatlardies.co.uk/blog/?p=5829

Coming up next will be photos of the two armies from these lists and some first games.

Showing posts with label South American Wars of Independence. Show all posts

Showing posts with label South American Wars of Independence. Show all posts

Monday, 16 May 2016

Sunday, 1 February 2015

New figures packs for the Liberation Wars range coming soon

We're excited to announce that we have several packs of new figures for the South American Liberation wars on the way. These include Peasants marching with muskets and also with bamboo pikes.

Along with a peasant command pack.

Also there are packs of Colombian infantry in fatigue caps and sandals marching,

and firing skirmishing.

Along with another command pack.

The advantage of both these units (the peasant militia, and infantry in fatigue caps), is that they can be used for both sides in both the northern and southern theatres of the Wars of independence, as well as for some units in the Peninsular War.

These are now being sent for casting, so we are hoping that these will be available for sale by the end of the month.

Along with a peasant command pack.

Also there are packs of Colombian infantry in fatigue caps and sandals marching,

and firing skirmishing.

Along with another command pack.

The advantage of both these units (the peasant militia, and infantry in fatigue caps), is that they can be used for both sides in both the northern and southern theatres of the Wars of independence, as well as for some units in the Peninsular War.

These are now being sent for casting, so we are hoping that these will be available for sale by the end of the month.

Labels:

28mm,

Gran Colombian Infantry,

Orinoco Miniatures,

Peasant Infantry,

South American Wars of Independence

Wednesday, 12 February 2014

200th Anniversary of the Battle of La Victoria, 12th February 1814

The Battle

As the sun was rising, at

approximately 7:00 in the morning of 12 February 1814, the spearhead of the

Republican forces located at El Pantanero spotted Morales’s forces moving in

from the south and west of the town. The first clash between the vanguard

forces occurred an hour later. Morales’s forces quickly pushed the defenders

back and took control of the positions near the Aragua River and on the heights

of El Calvario and El Pantanero, while the Republicans retreated behind the

defensive perimeter they had set up around the houses in the town surrounding

the main plaza.

In his book El General en Jefe José Félix Ribas, the

Venezuelan historian Héctor Bencomo Barrios describes the battle as follows:

The magnificent barrier of artillery fire and fusiliers, coupled with

existing obstacles, had turned the main square into a true stronghold. Nine

times the enemy cavalry charged, and nine times it was forcefully pushed back,

because the position was virtually impregnable to cavalry forces. Morales,

blinded by his ignorance of tactics and his thirst for blood, was incapable of

realizing this and obstinately tried to overcome the Republicans….

Edgar Esteves Gonzales, in turn, in his book Batallas de Venezuela 1810-1824, describes the events as follows:

The

infantrymen sought to protect themselves behind any breastwork they could find,

trying to hold off the waves of cavalrymen that came at them, one after the

other, with no surcease for the Republicans. Morales’s men doggedly attacked

again and again while the inexperienced defenders dropped one by one….

Yet another author, Juan

Vicente González, in his biography of General José Félix Ribas, published in La Revista Literaria in 1865, quoting

from Gaceta de Caracas number 42,

tells us that:

…nine times Morales charged and nine times he

was pushed back; the battle began at 8:00 in the morning and was fought on the

outskirts of the town, and was fought in the streets, where the enemy hordes

were finally able to penetrate; and was fought from the square, where the formidable

leader regrouped, uncertain whether help would or would not come, self-confident

and trusting to his luck. On horseback, in the midst of his soldiers, he

encouraged and drove them; he was everywhere; he held back and tired the enemy

forces. There was in his eye, in his speech, a spark that shone in those dark

moments; his look forced hearts to strive. Thrice the horse under him fell to

the ground; a thousand bolts of lightning flashed around the plumage on his

head, the target of every shot, heroically handsome and visible in the midst of

his comrades.

At approximately 4:00 in the

afternoon, following a frenzied battle, when the stamina and morale of the

defenders seemed to be flagging, a cavalry column approached from the west

along the Valencia-San Mateo road to attack Morales and his men from behind. It

was Campo Elías, the victor at Mosquiteros and avenger of those who had fallen

at La Puerta. He had marched from La Cabrera, some 40 Km. away, with two

cavalry squadrons consisting of approximately two hundred (200) horsemen under

the command of Manuel Cedeño and the brothers Juan and Francisco Padrón, as

well as two hundred and twenty (220) infantrymen under Lieutenant Colonel José

María Ortega and Captain Antonio Ricaurte, in aid of the Republicans. Rivas took

advantage of the confusion that reigned following the unexpected arrival of

help and ordered an attack, led by Major Mariano Montilla. One hundred lancers and

fifty light infantrymen broke away from their defensive positions and managed

to break through the ranks of the attackers, allowing Campo Elías’s troops to

breach the bulwarks. Reorganizing his forces in the main plaza, Ribas ordered a

general attack. Morales, who had no idea of the size of the forces attacking

him or whether additional reinforcements were on the way, was unable to

withstand the onslaught and, taking advantage of the waning light after sunset,

retreaded to the higher ground of El Pantanero, pursued by Mariano Montilla and

Vicente Campo Elías. Meanwhile, Boves, with the reserve forces, was approaching

along the road from Villa de Cura.

The battle ended with the

Republicans in control of the main plaza and Morales’s forces spread out in the

hills of El Pantanero. The next day, following the arrival of Boves at the head

of the reserves, the enemies of the Republic tried to regain the upper hand, an

initiative that was stymied by a group under the command of Colonel Campo

Elías, who defeated Boves’s men and sent them fleeing. Boves was forced to

return to Villa de Cura. One of the men to die in this battle was Rudecindo

Canelón, a captain in the Valerosos Cazadores battalion who had endured prison

in Puerto Rico and in Coro following the fall of the First Republic and had

been a heroic figure in the Battle of Araure.

The Republicans had suffered

serious losses. In his official report General José Félix Ribas said “We, in turn, lost some 100 men and have

close to four hundred wounded. Among the former, we must lament the death of

the intrepid commander of the “Soberbios Dragones de Caracas”, C.L. María Rivas Dávila; cavalry lieutenant C. Ron....” He goes on to report that

two horses had been killed out from under him, but that he had not been

injured. His report then goes on to say that no prisoners were taken “because our troops show no mercy....”

In the case of the death of the

commander of the “Soberbios Dragones de Caracas”, Luis María Rivas Dávila, who

was not a professional soldier but a lawyer from Mérida, and who had joined the

liberation movement when the Admirable Campaign passed through his city –and

who had distinguished himself during the fighting at Cerritos Blanco outside

Barquisimeto, protecting the withdrawal of the Republican troops, and at the

Battle of Araure- history tells us that when the bullet that would ultimately

kill him was removed, he held it up and said “Give it to my wife and tell her to keep it, and to remember that it is

to it that I owe the most glorious moment in my life, the moment when I died

defending the cause of my soil.” With his last breath he cried out “I die content. Long live the Republic!”

On the tactical side, we cannot

fail to point out that General Ribas made the best possible use of his forces

given the circumstances and the terrain where he was facing his enemy. By

placing his troops, mostly inexperienced infantrymen, in a defensive position

within a fortified square, he neutralized the advantages of mobility and brute

force that the cavalry gave Colonel Morales. The layout of the streets leading

to the plaza where Ribas mounted his defense offered the great advantage of

providing both the infantry and the artillery with clear, very specific fields

of fire that the enemy would necessarily have to follow during their approach

and attack. In the case of Colonel Morales, in view of the defensive position

adopted by his enemy, he should have reorganized his forces, launching attacks

mainly with the infantry and used his cavalry to prevent the arrival of

reinforcements that could attack him from the rear.

Although the Battle of La

Victoria was not a decisive encounter in the War of Independence, it was

extremely important from a strategic standpoint because it meant that

communications between Valencia, where the general headquarters were located,

and Caracas, the seat of the Republican government, remained open and prevented

Morales and Rosete from joining forces against the latter city, which would

have led to a defeat of the Republicans.

This episode in the War of

Independence has gone down in Venezuelan history as a most significant battle

thanks to the courage of the young university students and seminarians from

Caracas who, although not men of arms, did not hesitate to seize them and offer

up their lives in defense of the cause of independence.

In commemoration of the Battle of La Victoria and in

honor of the young men who fought there, on February 10, 1947, the National

Constituent Assembly proclaimed February 12th as Youth Day in Venezuela, “in

recognition of the services young people had rendered to the republic.”

Written by Carlos A. Godoy L. In commemoration of the 200 anniversary of the battle of La Victoria. Caracas, Venezuela. January 2014

Plaza Jose Félix Ribas, La Victoria, Venezuela

Written by Carlos A. Godoy L. In commemoration of the 200 anniversary of the battle of La Victoria. Caracas, Venezuela. January 2014

Labels:

Battle of La Victoria 1814,

Colonel Morales,

General Ribas,

José Tomás Boves,

South American Wars of Independence

Monday, 3 February 2014

200th Anniversary of the Battle of La Puerta, prelude to the Battle of La Victoria

Strategic Situation

Activities in the year 1814 began in the provinces of

Mérida, Trujillo, Caracas, Cumaná, Barcelona and Margarita, under Republican

control, although a number of guerrilla groups that sided with the Monarchy

were also quite active with backing provided by Brigadier Ceballos from Coro

and by Brigadier Juan Manuel Cajigal, who arrived from Puerto Rico towards the

end of 1813, as well as other forces active in the eastern and central plains,

with support received from Guayana.

Domingo de Monteverde, having suffered serious injuries in

the fighting at Las Trincheras remained under siege at the fortress in Puerto

Cabello after, in command of the Granada Regiment and other troops.

A man whose name would later fill Republican hearts with

fear was already being mentioned on the plains of Guárico. He was General

Commander of the Calabozo Cavalry (appointed by Monteverde in January 1813),

and later head of the Royal Army of Barlovento, José Tomás Boves, who

controlled the area around San Juan de los Morros at the head of an army of

some 3,400 men, mostly on horseback. This army, made up mainly of plainsmen, or

llaneros, and slaves who were promised their freedom provided they rose up in

arms against their former masters and in exchange for a share of the booty, was

neither American nor Spanish, royalist or republican, but remained on the

sidelines of the clearly differentiated forces envisaged by Bolívar when he

issued his Decree of War to the Death (Trujillo, 15 June 1813), and would soon

spread terror throughout the territory held by the Republicans, with anarchy as

its banner and “Death to Whites” as its battle cry.

The first battle of La Puerta was fought on 3 February 1814.

It was fought in a pass in the mountains that stand between the plains and the

northern territory, a crossroads for routes joining north and south and leading

to the valleys of Aragua and the roads to Valencia and Caracas, a site of

strategic importance.

The forces sent by Bolívar to fend off the threat of Boves

totaled some 1,800 men, mainly infantry, under the orders of Vicente Campo

Elías who had defeated Boves a few months earlier in the fighting at

Mosquiteros, in Guárico (14 October 1813).

This time luck was not on Campo Elías’s side. The Republican

troops were trounced. The combination of cavalry and numerical superiority of

Boves’s forces was decisive for this victory, which would not be the last the

enemies of the Republic would be able to boast of on this battlefield.

Campo Elías and his surviving troops retreated northward to

the town of El Consejo and then, under orders from Bolívar, to La Cabrera,

where he joined forces with the men led by Lieutenant Colonel Manuel Aldao, who

had been ordered to defend the strategic mountain pass.

Boves, who had been seriously wounded at the Battle of La Puerta,

was forced to head back to the plains to recover from his wounds and raise more

troops. Before pulling back, he split his forces. One column led by Francisco Tomás Morales,

with 2,500 men (app. 1,800/cavalry + 900/infantry) who were supposed to move

north, take the town of Villa de Cura and continue on towards La Victoria in

order to cut off communications between Caracas and Valencia; and another under

the command of Francisco Rosete (app. 2,000 men, mostly cavalry), who were to

march to Caracas via the Tuy Valleys.

When Bolívar received the news of Campo Elías’s defeat at La

Puerta, he set off for Valencia with part of the forces that were laying siege

to Puerto Cabello, a strategic move that placed him at the “center” of the

field of operations, where he would be able to head over to Barquisimeto to

help Rafael Urdaneta or move to Caracas if necessary.

At the same time, Major General José Félix Ribas, as

Commander and Governor of the Province of Caracas, moved the troops under his

command, intending to reach the town of La Victoria so as to ensure that

communications between Caracas and Valencia were not disrupted.

The troops under Ribas consisted of:

1) The La

Guaira Infantry Battalion, under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Ramón Ayala

Soriano, consisting of close to 350 men.

2) The Superb

Dragoons of Caracas, led by Colonel Luis María Rivas Dávila, with close to 200

men.

3) An artillery

battery made up of five (5) pieces of artillery and approximately 150 men.

4) Eight

hundred (800) students from the university and seminary in Caracas.

5) 200

unattached men and recruits.

By the time they reached La Victoria on February 10, 1814,

they totaled some 1,500 men. (For information on the number of men, we

recommend the book El General en Jefe José Félix Ribas, pp. 120 and 121, by

General Héctor Bencomo Barrios).

The Battlefield

La Victoria is a town that runs from east to west, about

midway on the main road joining Caracas and Valencia, some 80 Km. from each

city. To the west of the city lies a natural boundary, the Aragua River that

crosses the road about one (1) kilometer from the town’s main square. To the

north, it borders on the hills known as El Calvario that stand between the town

and the Caribbean Sea. Other hills,

called the Pantanero Hills, lie to the south, separating the town from the

central plains, and to the west lays the road leading to the Caracas Valley.

Tactical Situation

Upon arriving at La Victoria, General Ribas began to prepare

his defense strategy, aware as he was that his inexperienced infantrymen would

be unable to stand up to the cavalry on open ground and could suffer the same

fate as Campo Elías at La Puerta. He positioned his advance troops close to the

river’s edge on the main road, and on the higher land at El Pantanero and El

Calvario, setting up a fortified perimeter around the main plaza and the church

in town. He set up the artillery pieces, dug trenches and built breastworks to

protect the Fusiliers and the Dragoons. This was how things stood when General

Ribas addressed his troops, with the rousing words quoted by Eduardo Blanco in

his book Venezuela Heroica:

Soldiers: The long awaited moment is here today: there is

Boves. The army he brings to do battle against us is five times larger; yet it

still seems too small to wrest victory from our hands. Defend the lives of your

children, the honor of your wives, the soil of the motherland from the fury of

tyrants; prove to them that we are all powerful. On this memorable day, we

cannot choose between death and victory: victory must be ours! Long live the

Republic!

In the other camp, Colonel Morales, who would rise to the

rank of field marshal and who had abandoned the positions he held in La

Victoria before the arrival of the Republican troops, preferred to attack

rather than be attacked given that most of his troops were cavalrymen. He

therefore split his forces into two (2) columns. The first, marching in from the

southwest along the El Pantanero road, consisted of seven hundred (700)

infantrymen, two thousand (2,000) men on horseback, and four (4) pieces of

light artillery. The other, consisting of two hundred (200) infantrymen and

five (500) hundred men on horseback, moved in along the main road. Boves was in

Villa de Cura, recovering from his wounds, with a reserve force.

This was the setting of a battle that could decisive for the

future of the Republic. A Republican defeat at La Victoria would open up the road

to Caracas through the Valleys of Aragua, leaving the city surrounded and at

the mercy of Boves’s troops; this city also faced a threat from the south,

where Rosete was marching towards Caracas at the head of a column of 2,000 men,

leaving terror in his wake as part of the War to the Death.

Written by

Carlos A. Godoy L.

In commemoration of the 200th anniversary of

In commemoration of the 200th anniversary of

The Battle of La Victoria.

Caracas, Venezuela. January 2014.

Sunday, 8 December 2013

New Spanish Infantry with an ink wash

So here are a few new images of the Spanish

infantry after I managed to give them an ink wash this evening. I think

you can appreciate the level of detail, and the quality of the casts in

these pictures. These troops are in the short jacket common amongst the Spanish Royalist Army in Central and South America. They are also suitable for the Peninsular War, especially some newly raised Spanish units from 1809-1812, or regular Spanish or French Infantry fighting just in their waistcoats (many units discarded their tunics in battle due to the heat in Spain). I hope you like them.

The figures can be purchased directly from our webstore here:

Friday, 6 December 2013

Spanish Infantry now available for sale

I would like to announce that the packs of Spanish infantry (4 packs: Command, Flank & Centre Companies, and skirmishers) are now available for sale at the Orinoco Miniatures web store . I do hope you all like them.

The figures can be purchased directly from our webstore here:

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)